George Turnbull arrived in India in 1851, tasked with building its first long-distance railway. Born in Scotland, he had made his name as a civil engineer in England. After first training under the eminent engineer Thomas Telford, Turnbull was involved in major industrial projects including Middlesborough Dock and London’s King’s Cross Station.

Map of the East Indian Railway

1846, paper, card & linen printed by J .& A. Walker

The East Indian Railway was a project on an entirely different scale: it sought to connect Calcutta (the capital of British India) with Delhi (the capital of Mughal India). These two cities lay over 800 miles apart. By comparison, the Great Northern Railway, which Turnbull was also involved in, sought to connect London and York, two cities less than 200 miles from each other.

The British governed India by paper as much as by force. Reams of it circulated in the form of records, contracts and trade receipts. Taxation and other methods of extracting wealth likewise relied on paper.

Paper also created a visual record. While in India, Turnbull collected drawings and watercolours made by his colleagues, such as the landscape above, creating an archive that depicts the region from the perspective of the British engineers building the East Indian Railway. These works were acquired in 2017 by the National Railway Museum, part of the Science Museum Group. They have never been publicly displayed.

By the mid-nineteenth century, views of India had become a popular genre of picture. Often produced by amateur artists, these travel pictures held wide appeal to British audiences, transporting viewers to faraway lands from the comfort of an armchair at home. Architectural studies, such as the one above showing a mosque in the eastern Indian town of Rajmahal, were particularly popular. The artist, Alfred Vaux, was a resident engineer on the East Indian Railway.

The Mughals built Rajmahal’s Singhi Dalan palace in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It served as the private residence of Sultan Shuja, a Mughal prince and governor of Bengal. By the time Vaux made this drawing of the palace in 1856, the East Indian Railway Company was using the building as the district engineer’s private residence.

Building the railway was not always straightforward. The swamplands near Rajmahal made construction complicated. This bridge was crucial in attempts to plot a route for the railway. Turnbull followed existing roads through the flooded lands, passing over old bridges. He believed this held the key to finding a viable route, writing in his autobiography that ‘where they [the Mughals] could make a road we [the British] could make a railway.’

The colonial-era railways are often understood as a British invention taken to India, but they equally relied on existing local knowledge and technology. The old bridges were usually blanketed in overgrown vegetation, but some, like this one painted in watercolours by an assistant engineer, stood uncovered – with their detailed Mughal designs fully visible.

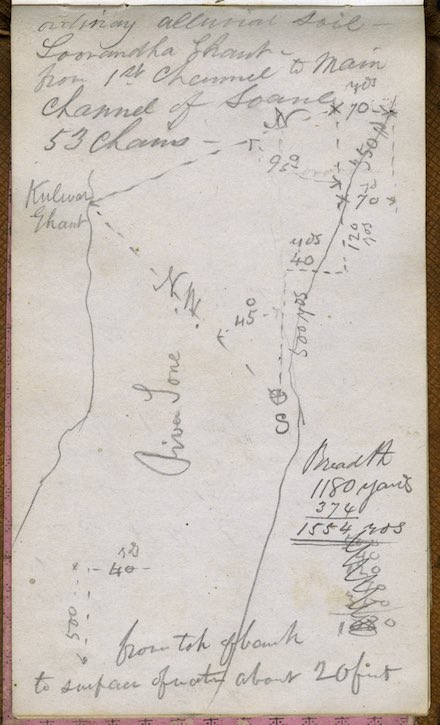

Page from George Turnbull’s 1851 notebook

As Turnbull plotted the railway’s route west toward Delhi, he encountered a larger obstacle: the Sone River. He would need to design a bridge. On 17th February 1851, he visited the site of the crossing and calculated the distance required, as shown in this page from his notebook.

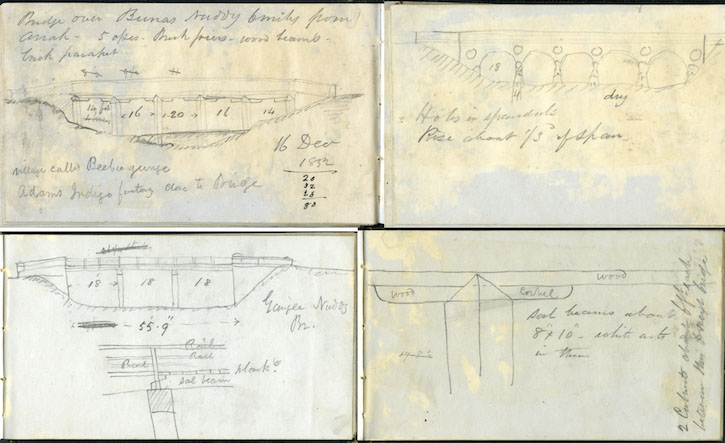

Selected pages from George Turnbull’s notebooks, 1851–1855

At over 1.6 kilometres, the Sone Bridge would be the longest river bridge in India, and the second longest in the world. Turnbull spent the next four years collecting bridge designs from the local area as inspiration, a selection of which are shown in pages from his notebooks.

During the 1840s in Britain, artists including John Cooke Bourne and Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait had popularised visual depictions of railway construction. This drawing, by Bourne, is in the collection of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum.

Building on that genre of railway construction picture, this watercolour of the Sone Bridge was painted in 1860 by the project’s lead engineer. The circular supporting blocks were Turnbull’s innovation; compared to rectangular designs, they are less likely to crack and sink into the ground. The image uses the vanishing point to emphasise the bridge’s impressive span: it appears to carve forward into the landscape. The emphasis is on how this man-made structure is overcoming nature’s hurdles.

Construction on the bridge began in 1856 but was disrupted in 1857 by the so-called Indian Mutiny, a widespread revolt against the British, in which rebelling Indians removed materials from the bridge. Construction restarted after the British suppressed the revolt. The bridge was opened in 1862 by Lord Elgin, the Viceroy and Governor–General of India.

Other works in Turnbull’s collection portray different manufacturing processes that were integral to the construction of the railway. The extractive force required by the large-scale industrial project is clear. With trees towering above them, workers collect materials in the middle of an old-growth forest previously undisturbed by industrial development. The huge bodhi tree on the right epitomises this tension between nature and industry. Sacred in Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism, here the tree teeters dangerously close to the extractive project at work.

Likewise, this watercolour depicts construction of the railway in Connagore (now Konnagar), a town on the west bank of the Hooghly River. The works manager, shielded from the sun by a servant, admonishes one of his workers. His residence, from which he has perhaps just appeared, is visible in the middle ground. Around him, anonymous Indian workers dig and carry dirt, the railway embankment stretching as far as the eye can see. This is a picture about surveillance, servitude and productivity, revealing the power dynamics that pervaded the colonial industrial complex in India.

Halfway up the image, water is visible. Konnagar is a wetland, with many flooded areas. The railways, in combination with other industrial development, blocked the natural drainage system. Things only got worse after the British Raj sold off surplus railway land in the mid-1870s, with development by private owners further cutting off the drainage system. Digambar Mitra, the first Bengali Sheriff of Kolkata, predicted that with this blockage ‘the epidemic will break out with greater virulence after the next rainy season than it has done before’. Sadly he was proven correct, and people who could afford to move away from the area began to do so.

This drawing of resident engineer Walter Bourne spotlights one of the people at the heart of the railway’s construction. Turnbull described Bourne as a ‘valuable’ man, yet this slapstick caricature portrays him as a bumbling, work-shy bureaucrat. Finding humour in exaggeration, caricatures focus on identity and individual character – quite the opposite to the anonymised Indian labourers depicted in the works above. With his half-eaten picnic beside him, Bourne’s hat tumbles off as he hurriedly writes ‘receipts for houses pulled down’ in nearby villages. The drawing alludes to the destruction wrought by the railway on the lives of many Indians. But the loss of peoples’ homes is reduced to mere paperwork – and played for laughs.

This collection of drawings and watercolours provides a view of the construction of India’s first long-distance railway in the middle of the nineteenth century. Documenting some of the project’s successes and challenges, it also reveals the impact this industrial project had on people and the environment in these regions.

Surya Bowyer, exhibition curator

See the Turnbull Collection in dialogue with contemporary artworks in ‘Paper Cuts: Art, Bureaucracy, and Silenced Histories in Colonial India‘ at Peltz Gallery until 12th July 2024

Further reading

A. C. Benson and Reginald Brett (eds), The Letters of Queen Victoria, Volume 3: 1854–1861, Cambridge University Press, 2014

Bholanauth Chunder, Raja Digambar Mitra, C.S.I., His Life and Career, Hare Press, 1893

G. W. MacGeorge, Ways and Works in India: being an account of the public works in that country from the earliest times up to the present day, Archibald Constable and Company, 1894

Aparajita Mukhopadhyay, Imperial Technology and ‘Native’ Agency: A Social History of Railways in Colonial India, 1850–1920, Routledge, 2018

Vineeta Sinha, Temple Tracks: Labour, Piety and Railway Construction in Asia, Berghahn, 2023

Michael Truscello, Infrastructural Brutalism: Art and the Necropolitics of Infrastructure, MIT Press, 2020

George Turnbull, Autobiography of George Turnbull, 1809–1878, Cooke & Company, 1893